Abstract.

This subjective, ethnographic study seeks to examine the

effect that the social setting of licensed betting offices has upon the gambling

behaviour within them. The study highlights many themes and processes in terms

of gambling as a whole which reinforces much of the current literature, such as

the decision making, or risk taking elements in gambling; discussions of that

which motivates people to gamble; and more quantitative analyses of who

participates in gambling behaviour. It locates all of the above within the

unique setting of the licensed betting office. The study identifies the plethora

of rituals which exist within this social setting and that influence the manner

in which punters, betting office jargon for customers, make their selections,

especially with reference to subjective probability and the illusion of control.

It suggests that whilst some of the discussions surrounding that which motivates

people to gamble bear weight in the context of licensed betting offices, some

may not be entirely universal. The study also attempts to identify how exactly

the licensed betting office affects who precisely gambles there. The study

investigates the manner in which the structures of betting offices come to offer

regular punters a particular sense of identity. Lastly, it raises the issue of

whether the social dynamic and sense of identity prevalent in LBOs will change

due to the recent developments in people's attitudes towards gambling, and if

so, which new groups who are likely to become involved in LBO gambling in the

future.

A Brief History of Gambling.

The Past

"And they crucified him. Dividing up his clothes,

they cast lots to see what each would get." (Mark 15:24)

Since the beginning of recorded history gambling has been a

prominent feature of many societies. The impact of gambling over the years has

ranged from answering questions about the world to rather less grandiose, but

still interesting achievements. Tomb paintings from ancient Egypt depict an

early form of dice throwing, using the ankle bones of sheep as the die; the

ancient Greeks believed that the mighty gods Zeus, Poseidon and Hades divided

the realms of Heaven, the Oceans and the Underworld between them on the casting

of lots; whilst as the above passage relates, the Roman soldiers who crucified

Jesus Christ resorted to a game of chance to decide who would take his seamless

undergarment as a trophy (Bernstein 1998: 1315). In 1654 the Chevalier de

Mérér, a well-known gambler, sought the advice of the great mathematician,

Pascal, on how best to divide the gains in games of dice. This proved to be a

major step on the path to developing the immensely significant theory of

mathematical probability (Cohen and Hansel 1956:1). The notion of attaching

numerical values in order to give meaning to the probable outcome of a given

event is as will be examined later, a fundamental aspect of the betting office

dynamic.

The evolution of gambling upon horse racing is characterised

by a curious balance of moral crusading and bowing to the demands of those who

wished to gamble. Around the time of the industrial revolution gambling was

scorned upon by the increasingly influential middle classes. They sought to

impose order and control over the lower classes whilst curbing the excessive and

frivolous habits of the gentry. The dominant discourse surrounding gambling was

one which depicted a ruinous path, comparable to the vices of alcohol and

promiscuity and which ran contrary to the rationalistic ideals of the

enlightenment (Clapson 1992:2). However, gambling upon horse racing had always

been popular among the upper classes. The weight of popular demand led to the

passing of the 1853 Betting act which permitted on course betting (only betting

with licensed bookmakers on the actual site) at horse meetings (Ibid. 108). A

number of "cheating" incidents and other organisational discrepancies

led to the gradual departure of the old upper class administrations and an

injection of middle class money and personnel into the enterprise of the sport.

This brought a more business like approach to the organisation of the sport,

which filtered into the legitimate betting industry. By the mid-late nineteenth

century, betting had become mass commercialised and the financial mainstay of

horse racing (Ibid. 133).

Greyhound racing reached the peak of its popularity in the

inter-war years. Originally being the savage pursuit of live bait, enjoyed by

the upper classes, the sport became far more humane. The middle class

humanitarian league put much pressure on coursing by suggesting that hares were

no longer being spent to test the dogs, but rather to facilitate gambling.

Meanwhile the RSPCA commended whippet racing, the lower class' answer to hare

coursing, as it used artificial quarry. The introduction of the electric hare in

1926 meant that now the greyhounds could be raced in a humane fashion (Ibid.

141-2). In the inter war years the social nature of the night at the dogs

fulfilled a dual function: it embodied the sense of relief of the armistice

whilst the gambling opportunities served to replicate the risk and uncertainty

of the war (Ibid. 143).

The Present

"Within a few years, gambling has changed from a

specialised activity, mostly for regular gamblers, to a mainstream

pastime." (Mintel Marketing Intelligence 2001:17)

The Betting and Gaming act of 1960 legalised off course

gambling in Licensed Betting Offices (hereafter referred to as LBOs). At their

inception, moral crusaders were still hailing the ill nature of gambling and

consequently great efforts were made to ensure LBOs were uncomfortable and an

unattractive place to spend time. Despite this "spit and sawdust"

approach, various subsequent acts of parliament have allowed LBOs to improve

their facilities such as introducing live television pictures of the day's

races; permitting the sale of light refreshments and affording the great luxury

of allowing windows to be unblocked. In addition, restrictions on LBO opening

times have been lifted to the point where shops can open on Sundays, and during

the summer, punters can have a flutter on the UK evening races as well as the

daytime meetings. The legalisation of LBOs brought with it a growth in the

number of people who would bet off course. Previously, it had been difficult to

lay more than one bet per day however, after the inception of the act,

continuous betting became feasible as complicated meetings with the bookmaker

were no longer required: one could spend all afternoon in the LBO (Downes et

al 1976:119). In addition, whilst those who already were engaged in illegal

betting would certainly continue to bet, those who had previously wished to

participate, but were afraid of possible recriminations, could engage safely in

gambling (Ibid. 120). Lastly, in this connection, the situation of an LBO in a

high street, public setting attracted passing trade, just like any other shop

(Ibid.).

The inauguration of the national lottery in November 1994 had

a strangely dichotomous effect on the LBO industry. Whilst the customer base was

hit hard with people (initially) favouring the new "dream ticket" over

the LBOs, the fundamental ideal behind the lottery served to increase the

profitability of betting shops. The idea of the "big win" (vast

returns for a minimal stake) became prolific and filtered down into the LBO

industry. Consequently many bookmakers noticed a significant increase of full

cover bets such as Yankees, Canadians, Patents and so on. These are complicated

bets, which can have as many as 247 separate bets within them. Thus if two or

three selections come in the punter will gain some small return (usually smaller

than the total stake money) whilst should every selection win, the returns are

likely to be enormous, a clear example of a "big win." However, as it

is extremely rare for these types of bets to come in, they are extremely

profitable for the bookmakers (Mintel Marketing intelligence 1998:22).

Furthermore, the long-term effect of the national lottery is likely to be

positive for the LBO industry as its incredible dissemination has served to

soften opinion towards gambling as a whole, whilst the vast number of players

has greatly increased the number of regular gamblers in the UK (Ibid.).

The increasing popularity of football in Britain, especially

since the apparent decline in hooliganism and the subsequent post-modernisation

of the game, is mirrored in LBOs where football betting is the fastest growing

form of gambling in the UK (Mintel 2001:13). The number of different ways to bet

are almost endless, ranging from merely guessing the winner, to accurately

predicting how many corners each team will be awarded (Ibid.). The new style of

betting comes to attract different types of punter, those who are not interested

in betting on the horses, but are willing to lay money on football results or

the middle classes, among whom especially, the increase in the game's popularity

is becoming apparent. The new types of spread betting, a new, complicated system

in which the punter bets against the bookmaker's estimate of, for example,

number of yellow cards, are becoming more prevalent but do not yet threaten the

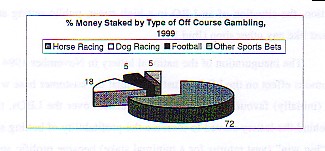

traditional betting methods. Despite this, however, horse racing continues to

dominate the amount of money staked in LBOs with dog racing a distant but

significant second.

The Future?

"People's perception of gambling has changed. It's

socially acceptable now because it's advertised on T.W' (Gamblers Anonymous

spokesperson. The Observer Nov 12 2000)

Despite the improvements made to the facilities of many LBOs

and the softening of public attitude towards gambling, it is still difficult for

LBOs to attract &new" customers from differing backgrounds. This is due

to the lingering persistence of their seedy image (Mintel 1998:25) and the

complex rituals surrounding making a bet (Neal 1999). The growth of the

inter-net gambling, telephone betting and iDTV (interactive digital television)

aids the opening of various new channels of distribution, along with improved

accessibility and anonymity: people are now able to sit in the comfort of their

living rooms and make bets, without interacting with anybody else. Further, the

increase in Internet gambling sites will serve to raise the image of the

industry which is likely to facilitate the growth of high street LBOs (Mintel

2001:17). As people from groups who traditionally shy away from the LBO become

more comfortable with the idea of betting over the World Wide Web, so they will

become less insecure about entering such an environment. The abolition of the 9%

betting tax on either stakes or returns, due to be instigated on October 6 2001,

is likely to increase the LBO turnover further.

A Review of the Literature.

This literature review seeks to examine some of the prominent

theories on gambling behaviour. I feel this examination is necessary as many of

these theoretical positions are prominent in my later observations. Further, the

vast range of differing ideas and explanations discussed below, will go some way

in demonstrating the incredible complexity of the umbrella term

"gambling."

Risk and Decision Making.

The study of gambling offers insights into a vast number of

sociological concerns, such as the changing nature of masculinities or the role

of sport in modem societies (Neal 1999). Risk assessment in everyday life is one

such issue which I seek to examine here, as the concept of risk is not only

pertinent to LBO gambling, but is also an increasingly important theme in

sociology as a whole. Ulrich Beck's (1994) work focuses upon how late-modem

society has become a risk society. Whereas in pre-modem times hazards were

tangible, the ongoing process of modernity has brought a change their nature.

They may be invisible, intangible and respect no borders. Risk becomes a way in

which we deal with the hazards and insecurities induced by modernisation (Beck

1994:21). Further, as these hazards and risks become more and more prolific, so

people become de-sensitised and ambivalent towards them: "Where everything

is a hazard, somehow nothing is dangerous anymore" (Ibid. 36). Thus Beck

provides a macro model, whereby taking risks is an insidious practice, leading

to the generation of gross hazards which threaten the very existence of

humanity, but is an inherent feature of the modernisation process. Lupton

(1999), however, presents a micro argument which highlights the positive aspects

of risk taking. She discusses the manner in which taking risks at the individual

level can be a means to escaping the restraints of mundane everyday life. She

suggests that "this discourse rejects the ideal of the disembodied rational

actor for an ideal of the self that emphasizes sensual embodiment and the

visceral and emotional flights produced by encounters with danger" (Lupton

1999: 149).

The most significant aspect of risk discourses in relation to

gambling is the allusion to the possibility of controlling, or foreseeing, the

outcome. The notion of taking a risk inherently suggests the weighing up of the

situation and making a decision based upon some knowledge. Much psychological

research has focussed upon decision-making and risk judgements as a conscious

action, whereby a selection is made by concentrating on the reasons which

justify this choice over another (Finucane et al 1996: 413). However,

Finucane et al (1996) argue that the affect heuristic in judging risks

and benefits is equally as important as cognition. The process of making

selections which may have positive or negative outcomes is not based solely on

conscious, rational choice, but rather on the way a person feels about the

decision. They suggest that images which are "marked by positive and

negative affective feelings guide judgement and decision making" (Ibid.

415). By approaching decision-making and risk judgements in this way, we can

answer a paradox with which a purely cognitive explanation struggles: why people

inversely correlate risk and benefit in their minds:

"... the relationship between perceived risk and

perceived benefit was linked to an individual's general affective evaluation

of a hazard. If an activity was "liked" people tended to judge its

risk as low and its benefits as high. If the activity was

"disliked" the judgements were opposite - high risk and low

benefit." (Ibid. 416)

This approach is closely linked to that of subjective

probability. Where mathematical probability represents rational objectivity,

subjective probability is the weighing up of probable outcomes in people's

minds, based upon imperfect knowledge. The major distinction between the two

types is the human inability to judge a series of events as independent

outcomes, for example, after a run of failures a success is "bound" to

follow (Ibid. p 10, Slovic 1996:11). In terms of gambling, the human incapacity

to comprehend outcomes as independent coupled with unpredictability (the very

essence of gambling) becomes manifest in discourses of knowledge, luck and

destiny (Cohen and Hansel 1956:143). Consequently, when gambling, rational risk

assessment is replaced with quasi-rational analysis of form combined with

non-rational feelings which guide and inform selections. Winning, therefore,

comes to be associated not only with sagacity but also with a sense that this

was something "due" to the gambler. Losing, conversely, reflects

stupidity and an event which is destined to change in the near future (Ibid:

147). Langer's (1983) work adds to this by suggesting that the close association

of skill factors and chance factors in people's minds results in a great

difficulty in discriminating between them. She deems the result the

"illusion of control" whereby the decision maker (gambler) believes

s/he is in control of the situation and can accurately predict the outcome

(Langer 1983:34).

Motivations for Gambling Behaviour.

Nowhere in the literature surrounding gambling is the

complexity of the issue better highlighted than in the proliferation of

explanations and theories about that which motivates people to gamble. Smith and

Preston (1984) offer an eleven fold typology ranging from psychological issues

of masochism and guilt, to sociological explanations such as escaping the

drudgery of daily life (Smith and Preston 1984: 330). Many psychologists have

contended that gamblers partake in such activity out of a masochistic desire to

lose, based upon a subconscious act of rebellion against those who impressed

upon them sound ethics, usually the parents (Dickerson 1984, Bergler 1967).

However, it is worth keeping in mind that a great deal of psychological

approaches see gambling as a pathology, some kind of malfunction within a

person's psyche and not the pursuit of "normally" functioning humans.

Whilst this approach offers a possible avenue of exploration, my desire is to

examine gambling within a certain social framework and not solely from an

individual point of reference. Therefore it is not attended to here.

Various studies have alluded to the social nature of

frequenting bookmaker's shops as a strong motivation to gamble. Zola (1964)

describes the friendships and group cohesion which result from punters

patronising the same establishment. Similarly, Rosecrance (1986) contends that a

major factor in the persistent gambling activity of regular bettors is the

sustaining function of the binding social ties formed there. He argues that in

off course bookmakers, certain cliques will routinely operate in order to

discuss the day's racing and form of the horses, using each other as

"sounding boards" for their selections (Rosecrance 1986:367). It is

worth keeping in mind that the above conclusions were based on research done in

the United States alone. Whether or not they relate to British LBOs will be

discussed in chapter five. Fischer's (1994) exploration into the culture of

fruit machine playing among British youths identified a distinctly hierarchical

social relationship between those players she termed as "arcade kings"

and their "apprentices." Here the relationship (as the categories

suggests) was one of the educating pupils, the price for such tuition being the

running of petty errands for the "king" (Fischer 1994:460). She also

distinguishes another important category, that of the "machine

beater," a lone gambler to whom no such social ties exist: they merely want

to win money and be left alone (Ibid: 462-3). Whilst Fischer's work is not based

in LBOs, it was based in the UK (unlike Rosecrance's and Zola's studies).

Chapter five will investigate which best describes the social nature of British

LBOs.

Common sense would suggest the role of desiring financial

betterment would be a prime motivational factor in explanations of gambling

behaviour. Staking a bet is an almost identical process to playing the stock

exchange, or investing in a business venture; one assesses the chances of

success and invests accordingly, hopefully resulting in some returns. Among

regular punters, the dream of the big win is prevalent, with punters often

compromising their pseudo-rational selection processes in order to select a

lively outsider, or "gamble" which will offer better returns for their

investment than the favourite (Neal 1998: 588). The inception of the national

lottery has compounded this fantasy (see chapter one) with a brilliantly

marketed message suggesting that one pound could win you millions (Mintel

1998:22). Further, Nibbert (2000) asserts that in Western societies wealth is

prized, labour is devalued and poverty is denigrated. In this context he argues

that it is unsurprising that people, especially of lower income groups, invest

not only money but also a great deal of emotional energy into such long odds

gambling (Nibbert 2000:45).

Closely linked to the idea of economic betterment is the

argument that gambling offers an escape from the frustrations of daily life

within the capitalist economic framework. In this sense, gambling functions to

divert the latent anger of the working classes by offering the opportunity to

make money in a fashion which runs contrary to the dominant discourse of having

to work to earn it (Smith and Preston 1984:328). From a more psychological

framework, gambling can be seen to relieve frustration by breaking down the

constraints of reality and allowing the gambler to "...dream luxurious

dreams not usually generated by the routine of daily life." (Ibid.) After

the wagering has begun, the gambler is transported to a fantasy world, where the

constraints of reality cannot impose themselves upon her/him (Ibid.). Similarly,

Goffman's theory of action suggests that the conscious subjection to personal

risk and uncertainty creates a thrill and excitement which allows the gambler to

escape momentarily from the mundane certainties of everyday existence:

'The individual releases himself [sic] to the

passing moment, wagering his [sic] future state on what transpires

precariously in the seconds to come. At such moments a special affective

state is likely to be aroused, emerging transformed into excitement."

(Goffman 1969:137 cited in Fischer 1994:449).

Goffman saw action as something positive and enriching within

people's lives. It provides positive excitement and variety within the lives of

gamblers. Thus, gambling provides a socially useful function for those who,

seeking action, choose to stake money on the unknowable outcomes of events (Neal

1998: 582).

Who Gambles?

A recent report, published by the National Centre for Social

Research, suggests that over fifty percent of the British population had engaged

in some kind of gambling activity in the week prior to responding to the NCSR

survey (Inter-net source). Around thirteen percent of the adult population had

bet on horse races (Ibid.) but twice as many men than women would pursue this

form of gambling activity (Sprotson et. aI 2000:1291). The only gambling

pursuit in which women are more likely to engage than men is bingo (Ibid.). This

is a long-standing observation as Newman's (1972) work records similar findings

(Newman 1972: 74). In terms of off course LBO betting, the distinction is vast

with men being over eight times as likely as women to bet in such a way (Downes et

al 1976:122).

Filby (1992) examines the highly gendered nature of LBOs in

his examination of sexuality within these shops. He firstly notes that the

overwhelming majority of punters are men, as are the managers of the shops.

However, the cashiers (lowest members are staff) are predominantly female (Filby

1992:25). Within the LBO setting, knowledge is highly gendered. Women, who have

traditionally been excluded from this setting, are assumed to have inferior

knowledge of LBO products for example, types of bets or what happens when a

selection becomes a non-runner. He observed that often punters would raise

queries with male staff, completely ignoring the female cashiers (Ibid. 28).

Filby argues that, in general, women do not understand the desire to bet. This

apathy towards gambling is due to the alleged stereotypical divisions which

gambling has been said to introduce into traditional working class families

(Ibid. 29).

Fischer (1994) draws upon Goffman's theory of action in a bid

to explain the massive discrepancy between male and female gambling patterns.

Citing Goffman, she contends that the quest for action is a predominantly male

concern: "... action in our western culture seems to belong to the cult of

masculinity." (Goffman 1969 cited in Fischer 1994:450). Fischer posits two

possible explanations as to why women are less concerned with seeking action.

Firstly, she argues that women are socialised into believing that seeking

gratuitous action is not appropriate to their gender. Secondly, she puts forward

the assertion that action as a concept is relative to the individual. As,

historically, women have been subordinated into performing mundane familial and

occupational roles, so they seek less dramatic action to relieve the drudgery of

everyday life (Ibid.).

Gambling permeates every strata of society, however, one's

social class is said to be linked to the type of gambling activity with which

one engages. Members of the upper classes tend to prefer casinos whilst the

lower classes would prefer 1J30 betting and Bingo (Inter-net source). Downes et

al speculate that "the use of betting shops increases as one descends

the current class hierarchy" (Downes et al 1976:123). They suggest that

where only four percent of the upper and middle classes frequent LBOs, some

thirty two percent of the lower working class use them. These figures apart, we

must bear in mind the recent developments within the history of gambling (see

chapter one). The inauguration of on-line and telephone betting makes it very

difficult to know exactly how many people bet whilst rendering any attempts to

analyse the class and gender backgrounds of these bettors virtually impossible.

Neal (1998) argues that different types of punter will use

the betting shop at different times of the day. He suggests that the morning

punters were mostly male pensioners who used the trip to the LBO as part of

their routine, often combining it with other tasks such as walking the dog (Neal

1998:592). Lunchtime punters were comprised mainly of low or semi skilled

workers who would place accumulated odds or pooled bets as they were unable to

view each race and could therefore not enjoy the excitement of betting horses

singly (Ibid. 593). Those who were unrestricted by hours of employment would

frequent the shops all afternoon, betting "race by race" (placing

single bets before each race and watching each event unfold) and achieving the

highest amount of excitement (Ibid. 594).

Research Design.

The research was conducted over a ten-week period, from early

June 2001 to mid August of the same year, in eight LBOs in and around the city

of Leicester. It is important to note that this period was unusual in terms of

the LBO industry for a number of reasons. Firstly, as this was the summer period

there would be two or three televised night racing meetings broadcast each week.

The LBOs would stay open for around four hours longer than they ordinarily

would, thus offering punters greater opportunities to lay their bets. Secondly,

and most significantly, the foot and mouth crisis had had an enormous effect on

British horseracing, with a number of major meetings being cancelled altogether.

This, in turn, had serious implications upon the LBO industry which depends on

horse races more than any other sport for its income. In an attempt to curb the

financial losses the Satellite Information Service (SIS), which broadcast the

live pictures to the LBOs, would televise a number of foreign meetings from

South Africa, the Middle East, Italy, France and especially from Ireland, in

place of the lost British racing (Mintel 2001: 10). In addition, a greater

number of dog racing meetings were also broadcast, to supplement the betting

chances offered by the foreign races (Ibid.). However, after the foot and mouth

scare had subsided enough to permit the re-opening of all British meetings, SIS

continued to show much of the foreign racing. This was due to the fact that SIS

were soon going to lose the broadcasting rights to the British meetings and were

thus "sounding out the punters to see if they would bet on the foreign

races even with a full British card. Consequently the punters were provided with

far more chances to bet on far more races than usual. These circumstances were

unique and may have had implications on the LBO industry, and gambling activity

during this period.

The punters that I was most interested in observing were the

regular gamblers. Regular is a particularly vague term so here I will stipulate

those who I considered to be regular gamblers. They were the punters who would

spend at least an hour in the LBO, betting race to race, whom I would see almost

every time I worked in their particular shop. They would know most of the staff

by name and would often chat to them in a fashion not dissimilar to how a

regular patron of a pub may talk to the bar-staff.

The research was conducted covertly with me attaining a job

with a leading high street bookmaker’s chain. I took the post as a cashier and

worked in eight shops around the district. These shops were all based in

residential areas around Leicester except for two, which were closer to the city

centre. In another three LBOs, I took the role of a punter in competing high

street bookmakers in order to try to get a picture of the social setting from a

different perspective, however, this approach was far less successful as the

time constraints of the research did not allow me to form the kind of social

ties that would allow fellow punters to talk to me about their gambling

behaviour. I felt that my approach was justified for a number of important

reasons. Firstly, it allowed me instant access to the field without having to

depend on the acceptance of punters in order for them to have to interact with

me. Punters are often secretive in their strategies for selections, however, as

a cashier they would have no choice but to reveal their bets to me as I was

responsible for processing them.

Secondly, LBOs are very ritualistic places (Neal 2001). In

order to be accepted, one must be well versed in the complex processes of

filling out betting slips. One must be familiar with the betting shop jargon

especially surrounding the plethora of terms relating to different types of bet,

form and prices. It is also important to know the rules of interaction, for

example letting someone who wants to get on the next race jump the queue, or

knowing how to discuss form "expertly." By entering the field as a

cashier, all of the above idiosyncrasies of the LBO were taught to me in a

three-day induction course, this meant that whilst I was certainly

"green" to begin with, it didn't take too long to be able to engage in

conversations with the punters about their betting. Further, in the capacity of

a flexi-time cashier, I worked all across the district, increasing the scope of

the research considerably.

In carrying out the research in a covert manner, I felt that

I would avoid many problems associated with validity. Respondents are often seen

to present answers to researchers which may be less than completely truthful in

order to make themselves look good, or bad, or whichever impression they are

trying to foster. This is closely linked to de Vaus (1993) notion of social

desirability, which, he argues, increases with greater personalisation (de Vaus

1993:110). Thus, if the punters were unaware of my position as a researcher,

there would be no reason for them to perform in a manner distinct from that

which they would in front of any other cashier.

When I first entered the field, I had no specific- question

in mind. I felt that it would be best merely to observe the dynamics of the LBO

and see how my examination of events tied in with the literature. As the

research went on I sought to place the literature in the context of the unique

setting of the LBO and compare this with my observations. I felt that this would

build upon that which has been written before and would thus go some way to

justifying the methods which I employed.

Research Experience and Methodological.

Problems.

Taking this project on was at once rewarding, yet difficult

and sometimes emotionally stressful. The research design which served to

eliminate a number of problems associated with access and authenticity led, as

is almost inevitable in social research, to a number of other difficulties.

Principally, there were issues concerning the practicalities of recording data,

subsequent analyses and ethics.

Recording data was very difficult given the circumstances of

the project. Being completely covert meant that I had no way of taking down

information first hand, in a survey style questionnaire or taped interview. As a

result, many of the observations made in the LBOs were noted down on scrap

paper, or betting slips and then taken home to be written up in a research

journal of the days events. The rest of the day's journal entry would be

comprised of events that I had observed throughout the day. Recording what

punters would say to me was extremely problematic as I was in no position to

take down what they said, due to my role dictating that I be engrossed in the

discussion as a real cashier would. Often I would be forced to make some excuse

to terminate the conversation (usually a trip to the toilet) so that I could

note what had been said whilst still fresh in my mind. Consequently, much of the

conversation I had recorded would be more like a "sound-bite" as I

could only accurately remember short phrases or dialogues.

The implications of the problematic nature of recording the

data were especially significant in terms of my analyses. As everything which I

had observed was based upon my own interpretation of events I can make no claims

to my conclusions being objective in any way. Anything which the punters had

said which was recorded would have only been that which I considered

significant. Whilst I disagree with the plausibility of producing any value-free

social research, I do find it a regrettable short-coming of this project that

the punters could not express themselves in their own words. However, I felt

that if I had revealed myself as a researcher later into the research and

requested interviews, I would have been unsuccessful as I would have been

exposed as a liar and deceiver, and breaching punter - staff social cohesion.

Further, in the unlikely event that anyone would have agreed to be interviewed,

I would have been faced with the same problems that this approach was supposed

to avoid, such as a possible lack of authenticity.

The practical difficulties in conducting this research were,

as indicated above, significant. The ethical dilemmas, which presented

themselves, however, were of even greater importance. Covert research is often a

very touchy subject within sociology. Treweek and Linkogle (2000) have

implicated the barbarous medical experiments, conducted by the Nazis in the

second world war in a shift from an emphasis placed upon the researcher's right

to discover information at any cost, to today's prevalent perception that any

research must first and foremost guard the rights of the subject (Treweek and

Linkogle 2000:17). This includes attaining informed consent, by which the

subjects are aware precisely of that which the researcher is investigating and

only take part if they so desire. Covert research clearly denies this

opportunity to the research subjects. However, there are occasions where the

researcher may be unable to gain access to the field unless s/he conceals

her/his true motivations from their subjects. For example, Calvey (2000)

contends that he would have been unable to produce his study of nightclub

doorman had he chosen any other method than an undercover approach. I feel that

I was justified in using a similar approach as I could not have gained access to

the number of LBOs, nor attained an authentic picture of LBO dynamics any other

way.

Despite rejecting the plausibility of conducting the study

through informed consent, I feel that this research still protects the punters

at the core of its findings. I have made certain that all parties remain

anonymous, and have further made sure not to include any comments or quotations

which may disclose the identity of the punter. A great deal of the research

focuses on the way gamblers behaved within the context of the LBO, which also

goes some way in de-personalising the study, as it tends not to concentrate on a

single punter.

Many commentators have objected to the way in which covert

research hinges upon deceit and false presentation of oneself.

O'Connell-Davidson and Layder (1994) argue that when researching covertly, the

researcher must continually reproduce the deception of subjects in order to

maintain their acceptance, and consequently, ensure that access to the field is

not disrupted (O'Connell-Davidson and Layder 1994:171). This clearly puts a

great deal of strain upon the researcher as the entire project comes to depend

upon this process. In terms of this research, the deception of the punters was

easier to bear than that of my colleagues. Often punters would only ever discuss

their bets or certain races. The staff however, were much more interested in

things outside of work and would often ask questions about my personal life.

Whereas they were aware that I was a student, they never knew about the

research. As many of the staff had become friends it was an emotional strain to

actively have to lie and deceive them on a daily basis.

With reference to the above-mentioned ethical considerations,

the value of the research is often called into question. Various studies in the

past have become benchmarks for how not to conduct social research. Burgess

(1984) cites Warwick's (1973) fierce criticism of Laud Humphrey's now infamous

The Tearoom Trade in which Humphrey's covertly investigated homosexual activity

in public conveniences, by posing as a "watch queen," a voyeur who

kept guard:

"Should every social scientist who feels that he [sic]

has a laudable cause have the right to deceive respondents about the nature

of surveys, engage in covert observation and resort to other kinds of

trickery?" (Warwick 1973 cited in Burgess 1984:188)

Whilst this is a well-supported comment, there are occasions

where covert methods are justified. This research may not be groundbreaking, yet

it has value in that it provides some kind of insight into an area of society,

which has not been investigated to the same extent of other facets of society.

However, the study of gambling opens up a host of other channels of enquiry and

thus, if the research is constructed so that it protects its subjects, it is

worthwhile. Further, as Bronfenbrenner duly observes:

"The only safe way to avoid violating principles of

professional ethics is to refrain from doing social research

altogether." (Bronfenbrenner 1952, cited in Burgess 1984:207).

Clearly, this project was rife with ethical and practical

problems, none of which I pretend to have superseded. However, by acknowledging

the shortcomings of the project it retains some credibility in terms of a

subjective ethnographic analysis of a much neglected yet important facet of

society.

The Study.

"He had the idea that this was a science rather than

luck, that in some way he was more skilled than the average punter."

(Wife of a compulsive gambler in The Guardian 27 February 1996).

The most striking feature of all the LBOs in which I worked,

or visited as a punter, is their uniformity, not just in terms of corporate

colours or staff uniforms, but in a way which transcends the nuances of

different companies. On entering any LBO a punter is bombarded with information

as seemingly every square inch of the shop is utilise in order to maximise the

customer's capacity to check form or the anticipated/actual state of the betting

market. Each wall is covered by eye-level display pages from the day's edition

of the Racing Post. These sheets detail the vital information for the day's

horse and dog racing meetings such as best time, recent placings, age, weight,

who is the designated jockey, who is the trainer and so on. The bigger meetings,

or important races, are printed in colour to depict the silks each jockey will

be wearing but in the otherwise plain surroundings this also has the effect of

catching the eye. There is a brief summary of each runners chances followed by

the "verdict" which puts forwards the best selections and likely

winner. The state of the ground is given, as is a brief weather report. There

are data banks, best "placer" selection chances and even a small plan

of the course. No detail is left un-described.

These pages were the staple information source of the regular

punters, particularly of those who would come in before the afternoon racing

began, make their selections and leave soon after for work or other

appointments. Punters would scrutinise these displays as if they somehow held

the key to unlocking the guaranteed winners of the day. Different punters had

different strategies for decoding the information provided, or would concentrate

on distinct snippets of information, but almost invariably these pages were the

regular punter's first port of call in the ritual of making a bet. For example,

one punter was adamant that the "time to first bend" section for the

greyhounds was of great importance:

"There's always a couple you don't fancy and always

a couple you do so I check out the bend times and see which is most likely

to get fucked over on the first, then 1 put the money on the other

one."

Other punters would be far more concerned with their

selection's previously proven ability over the course of an entire race.

I always look at the previous race times over that

distance because it tells you what the horse can do, I mean, you wouldn't

expect it to do more than it has in the past, even if its been

improving."

The form guides, as the major source of information, were

clearly the key factor in the punters' quasi-rational assessment of each horse's

likelihood to win. However, the types of conclusion drawn from the same

information sources were as varied as if people hadn't bothered consulting the

form at all. As the guides offered a plethora of facts, figures and statistics

it became increasingly apparent that punters were only really being truthfully

guided by their instincts or that which they had subjectively concluded as the

best method for predicting the outcome of the race. Often punters would choose a

"system" for picking winners which would rarely change, regardless of

whether or not it had proven itself to be successful or not. Thus I was

increasingly convinced of the affective state, or subjective probability being

played out in the decision making process through these form pages. This

impression was strongly reinforced by a glib comment from one of my colleagues

to a punter who had been discussing with me favoured methods for picking a

winner:

"You can make it as simple or as complicated as you

like, but you'll never bloody win."

The other major influence on the decisions made by the

punters was the monolithic bank of television screens, common to all but the

smallest LBOs, which seem to occupy entire walls whilst showering the punters

with constantly updated information. They show the live broadcasts of the day's

racing; they depict race times and runners; they highlight numbers game results

(games provided by the broadcasting company based on random number selections)

and the latest betting opportunities as they become available. The latter

function, specifying the state of the betting market before the off of a race,

was by far the most significant in terms of selections made. The price (odds) of

a runner winning the race are not only compiled on the basis of the bookie's

assessment of its form, but also on how well it is being backed by the punters

on course, once the betting becomes available. Often, a well-backed selection

will see its price contract at a great rate. For example, a horse may start

betting as a 20-1 outsider, yet the more money that punters back it with, the

shorter the price will become so the bookie stands to lose less money should it

come in. Consequently it would become 16-1, then perhaps 10-1, 9-1 then may have

its starting price, the odds offered at the off of the race, at 17-2. This horse

would then become a "gamble" which would stimulate a dash to lay a bet

down before the price contracts any further. Being able to read the market (in a

more complex manner than suggested above) was a skill which often earned the

successful punter a great deal of kudos and often, when betting on a gamble,

punters would make casual references to what they were doing:

I'll take sixes (6-1) before it gets any shorter."

Further, there were occasions where the emergence of a

"gamble" would clearly prompt punters to bet on a horse that they

originally were going to reject.

"Might as well have fifty p each way on that one,

its come right down from twenty fives (25-1)."

However, there were also a number of punters who would bet on

runners whose prices had remained static since the start of betting. Theirs was

the logic that although no one seemed to be backing the horse, no one was

betting against it either. In addition, some punters would try to "hedge

their bets" by betting on a favourite, but also staking a lesser amount on

a gamble or outsider, "just in case."

SIS, which provided the live pictures of the day's races,

also provided the commentary and a pre-racing programme dedicated to expert

analysis of the race cards, ultimately leading to a specialist making a number

of likely selections. The analysis programme did not appear to have a great

effect on the punters, as it would rarely suggest any outcome other than that

which was already printed in the Racing Post. Further, most punters who would

come in for the afternoon races and bet race to race, would enter the LBO at

around one o' clock to one thirty, by which time most of the analysis had

finished. On many occasions, it appeared that punters were more interested in

the actual personalities who presented the show, rather than the tips they had

to offer. Often they would make comments about how the- "fool" on the

TV didn't have a clue what he was talking about or about how

"attractive" they found certain female presenters to be. I never heard

a punter suggest that the exposition had informed his choice, and rarely heard

any praise for the tipsters. The punters generally seemed to believe that they

knew more than the specialists.

The incessant commentary, however, seemed to have a much more

pronounced impact on influencing the punters' selections than the pre-racing

programme. In a manner similar to the bank of television screens, commentators

would constantly barrage the airwaves with statistics, facts and figures when

not describing the races. They would announce the selections that were being

well backed; they announced showcast prices which offered the punters odds on

forecast (correctly predicting first and second) bets before a, race, (which was

unusual as forecasts were usually based on dividends decided after the race,

based on how well backed the runners were); and they would even assess the

"form" of the balls in the numbers games such as 49s (SIS' answer to

the national lottery) a twice daily draw of six numbers followed by a

"booster."

"Red number thirty is in scorching form at the

moment, it’s been out in three of the last four draws."

Often, despite many punters acknowledging the near absurd

notion of a randomly generated number having "form," they often would

be interested to hear of so called "unlikely" outcomes. In one shop,

the lowest ball (1) was followed by the highest ball (49) amidst murmurs of

"what are the chances of that?" Although no punters ever told me that

they had decided to back a certain selection due to the commentary, there would

regularly be a number of punters who would bet on a gamble, or a showcast only

after the announcers had disclosed it.

The unrelenting exposure to facts and figures play no small

part in reinforcing the punter's illusion of control. The fundamental message

reproduced by the LBOs (and on-course gambling) is that there exists some kind

of science to the game, with which punters can realise their fortunes: they give

the impression, always, that there is a specialised knowledge which when gained

will allow the customers to "beat the book." The proliferation of such

statistics suggest a rational path through which placing a bet becomes a

measurable risk, rather than a pursuit of chance. However, despite this

discussion of form studying, there exists a major paradox in the culture of the

regular punter concerning the prices of selections. Often punters were reticent

to take short odds on favourites, or even selections they fancied, as such a

price was not going to earn them what they deemed sufficient returns. On many

occasions, punters would request a price only to be disappointed at that which 1

could offer them:

“Odds on?! What's the fuckin' point in betting

it?"

“Its not worth it, not at that price."

Thus, a punter who may have spent a considerable amount of

time studying form would come to reject the selection as its likelihood to win

were considered so high that any returns would be small relative to the stake.

Often punters would try "price pinching," stipulating on their slip a

better price than was currently offered, in the hope of it being processed at

those odds. This behaviour could have been due to a desire for the big win, or

even out of the psychological explanation of masochism. Whatever the reason it

was interesting to witness such a strange contradiction when the ceremony of

making a selection was undermined due to the apparent correctness of the

punter's prediction.

One such example was a punter who on the three occasions we

met would always discuss with me two very good horses (at the time of writing),

Galileo and Fantastic Light. He suggested that he would always back Fantastic

Light in any mile and a half race, so long as Galileo wasn't running. However,

when the two horses went head to head at the King George VI and Queen Elizabeth

Diamond Stakes he continued to back Fantastic Light because at 7-2 it was

"great value" whereas the 9-4 Galileo was not. Galileo won.

The Gamblers.

Not only do the LBOs rituals and set-up seem to exert

influence over the choices the punters make, it also tends to reflect who

gambles there. The notion that women are far less likely than men to bet on

horse and dog races, especially in off course LBOs, would be strongly supported

by my observations. The LBO is rife with a sense of traditional masculinity: its

physical appearance is bare and functional, providing only what the punters need

to select their bets. There are no attempts to brighten the space up; the walls

are plain save for the occasional bright promotional poster to draw the eye. The

space is perfectly utilised to balance the seating requirements, places to write

and sufficient space for punters to wander from form guide to counter and back

again. Quite simply, the LBO is laid out to allow the smooth operationalisation

of the betting ritual.

Every LBO is permitted to have two Amusement With Prizes (AWP),

or fruit machines. These often have different themes in order to differentiate

the almost identical technical principles behind them. Such themes were:

"king kebab" which depicted a stereotypical Greek kebab shop owner,

with "Donna' his young female assistant (wearing a short skirt and fishnet

stockings); "revolver" in which the player takes on the guise of an

international super spy; and "cashanova" upon which the player would

follow a "trail of love" (augmented by female moans of orgasmic

pleasure) to the strains of Spring from Vivaldi's Four Seasons on her/his way to

the jackpot. Thus it appeared that even the AWP machines were appealing to a

traditional sense of masculinity, with dominant men and subservient women, or

incorporating traditional "boys own" fantasies.

Finally, in this connection, interest in SIS' flagship

numbers game, 49s, had gradually been diminishing. During this research period a

new game, hatrick, was launched. The promotion of this game featured three young

women, all donning knee high boots, hot-pants and a "hatrick" top,

which was strongly based on a football shirt. It was clear that these girls were

being used to try to attract the male "race to race" punters into

playing the new game, as it was women who most often played the numbers game,

yet it did not seem at all out of place with the rest of the social environment.

The lack of female punters I observed in LBOs during the

research would seem to concur with the literature. I cannot suggest that the LBO

causes this major discrepancy, but I would confidently asset that it reinforces

it. Throughout the entire district, there were less than ten women who I would

consider regular punters, in terms of the frequency of visits and duration of

stay. These were the only ones who engaged in the form assessing processes, knew

about market movers and "gambles," and would bet race to race.

Interestingly, these women staked less than their male counterparts, rarely

exceeding two pounds. The clear majority of women bet on the numbers games,

especially 49s and the Irish lottery, and spent little time in the shops. The

most frequent pattern 1 observed was that a woman would enter the shop with a

number of pre-filled betting slips, pay for the bets and then leave. Often, the

trip to the LBO was combined with other tasks such as doing the grocery

shopping. An additional common occurrence would be placing a bet (pre-written)

for a husband or partner whilst they were out. Regularly, if I asked if they'd

like to take the price on a certain horse they would retort words to the effect

of. 'I don't know, he never said." Otherwise they would have been

instructed in advance:

"He wants the price on Orientor is it? Oh yes

(pointing to selection on slip) that's the one."

All but two of the LBOs in which I worked were located

outside of the city centre in residential areas. All but one of these was

situated in predominantly working class areas. The LBO which was situated in a

more affluent working class to middle class area was, interestingly, the

smallest and least profitable in the district. Consequently, the bulk of the

punters were of working class backgrounds. A number of regulars were unemployed

(at the time of writing) and would consequently have more time at their

disposal. The only punters who seemed to spend more time in the LBO than the

regulars who were currently unemployed, were those who had retired. Among the

other regulars were those with jobs which required them to move from place to

place and would spend some time laying bets between jobs. Others would come

during their lunch hour and after work, and a few were self employed within the

vicinity and would come and go as they pleased. Patterns of betting were very

similar to those observed by Neal: pensioners would come mainly during the

morning, staking small specialised full cover bets; lunchtime punters who were

on a break from work would spend an hour or so in the shop, again laying full

cover or accumulator bets, whilst the majority of those who bet "race to

race" were punters unconstrained by working hours.

Generally, the amounts the regulars would stake were

relatively low. Many would bet one or two pounds per race, others might stake

thirty pounds. The size of a large bet was anything from fifty pounds upwards.

My employers would "log" customer betting amounts of one hundred

pounds or over per race irrespective of which LBO s/he was patronising. This was

a good indicator of the expected affluence of any punter, and that the LBOs were

set up in similar areas of similar income groups. On the occasions where 1 took

substantially larger bets, for example a £1,000.00 single bet, people would

quickly become interested, often berating the punter for being foolish for

staking so much. This again highlighted the relative uniformity of the stakes

made by regulars.

Motivations.

The LBOs clearly presented themselves as places where money

could be won. The terminology, statistics form guides and so on all served to

promote the idea of betting, as discussed above, as a calculable science. Often,

when I asked punters why they chose to come to the LBOs, they would retort with

some sarcastic comment such as "why do you think?" Other times they

would be more hopeful, such as "you've got to try." In short, when

asked directly, they would almost always refer to some kind of financial gain.

Despite this, there were occasions when they would almost contradict themselves,

or be completely inconsistent with the motivations they had consciously cited

previously:

"I don't care what anyone says. No one could ever

make a living out of this, not really."

"No-one beats the bookie, no-one."

"I'm the best loser in this shop. Ain't that right

'Ethel'"

The overwhelming impression imposed on me by my observations

would tend to support the discourse surrounding gambling activity as a means of

escaping the drudgery of everyday life. As the literature suggests (which

concurs with this study) it was mostly lower class men who would spend time

betting race to race. Whereas there was obvious pleasure, and a lot of banter

with staff, when winnings were collected, especially when they were

significantly larger than the stake, the tension in punters during races was

immense. The punters seemed to experience a plethora of emotions all in the

space of a few minutes (or seconds in the case of the dogs), from hope, to

despair, from seeming defeat to victory. Punters would shout at the screen,

willing their selections on, even twitching with the tension. Losing was usually

followed with some profanity, screwing up the slip then making another bet.

Winning however, brought with it not just financial returns, but the

satisfaction of winning. In this context punters would present themselves in a

manner, which suggested that whilst they were in this LBO, they were a winner.

In a manner which would concur with Goffman's theory of action, the thrill of

watching the outcome of the race provided escapism from boredom and routine, the

thrill of winning provided a sense of being "someone," a phenomenon

which does not often happen in daily life. Other punters would react to the

winners in a number of ways. Members of the same clique (if s/he was in one)

would often enter some banter about being “Iucky," or words to the effect

that "you should have accidentally won by now anyway." Punters outside

of the winner's particular clique would often become briefly interested, yet

from a distance. They would regularly maintain an air of cool indifference, as

if assessing the winner's skill relative to their own. Rarely would

congratulations be offered by anyone other than staff or group members.

When the punters did lose they had a tendency to head

straight back to the betting slip dispensers. Although it could be argued that

they would merely be trying to make up their losses, which probably is the case

in many cases, the speed with which punters forgot their losses suggested that

it was not solely the losing of money, but the losing feeling they wanted to

dispose of. Further, punters would remember big wins for, literally, years,

often relating the tales of their winning as if they were some kind of fabulous

military victory. Thus, I felt that the feeling of winning was the key to

cherishing big returns.

The LBOs were paradoxically accommodating for the social and

leisure aspect of gambling, whilst simultaneously ideal for the lone gambler.

Most LBOs had large tables around which a group of punters could sit and discuss

the day's racing. One of the bookmakers chains had seating which was strongly

reminiscent of football stadia, with rows of plastic chairs facing the

television wall, with the back row resembling the leaning posts found in the old

terraces. Although not licensed to sell anything more than hot drinks, fizzy

pop, chocolate and crisps, many of the larger shops would offer these

facilities, almost adding a pseudo-bar aspect into the environment. In one shop,

a group of betting shop friends would do "rounds" for coffee.

There were a number of groups who would always meet up in the

LBO and enjoy the betting together, discussing form and so on. Often there was a

"leader" whose opinion was slightly more respected than the others in

the group. However, these groups only regularly came together on Saturdays.

Often the visit to the bookies would follow a trip to the pub to where they

would return after the afternoon racing. During the research I never noticed

such a gathering taking place in the week. In addition, despite debates within

the clique about which was the form horse, and despite the regular presence of a

leader- group members would rarely all back the same selection.

Most of the regulars I observed were not particularly

interested in the social side of LBO betting. They would be in the shops most

days, and would know each other but would rarely manage more than a nod and some

casual small talk. Sometimes there would be a brief chat about the chances in

the next race but primarily they were there to bet alone. For these regulars,

the staff were much more the focus of any sociability, but this would invariably

be limited to banter about prices or the time it took to settle a bet, or

discussions surrounding the events within a race.

"D'ya see that Owen, the fucker's lame!"

"Look at that there, look at the way he's coming

across him (illegally crossing in front of another horse) there, that's

fuckin' criminal that is!"

Regular punters were also very secretive and guarded in their

selection processes. Nowhere did this become more visibly apparent than in the

LBO custom of receiving a bet face down, and placing the processed copy on the

counter in the same way, or folded in half, in order that only the punter and

the staff know the selections on the slip. Thus I felt that these regulars were

far more interested in their own betting to help others, or talk to others.

These observations run contrary to the strong emphasis placed

on sociability as a motivation to gamble proffered by Rosecrance and Zola.

However, the "leaders" within certain cliques bore similar

characteristics as Fischer's "arcade kings" whilst the non-social

gamblers were akin to her "machine beaters." One of the older punters

was especially well respected by members of his own clique and by lone punters

due to his ability to read the market. He would often accurately predict when a

horse's price was going to ease or contract by observing the changing prices of

the other horses. Consequently he would often pick a horse at the highest price

available and many others would wait for him to place his bet before they would.

The LBO and Identity.

The findings of this research are rife with undertones of a

specific identity and culture, which exists in LBOs, that determine rules of

interaction and behavioural rituals within them. Burkitt (1995) contends that

there is no such thing as a pre-given or innate personality coming from within

us, but rather that identity is to be found in the social relations which exist

between individuals (Burkitt 1995:189). Further, as these relations occur within

certain material environments, the setting too becomes important in defining

identity. LBOs are a unique social environment, which contain structures that

help to maintain the culture and identity of the punter. Punters are

overwhelmingly working class men and within the LBO this identity becomes

manifest in a number of ways.

The traditional sense of masculinity within the LBO serves

not only to keep women out of the betting shops, but also to attract new punters

with similar traditional masculine ideals. Not only are the shops physically

uninviting to stereotypical feminine sensibilities, there exists a specialised

knowledge which is considered to be exclusively male (Filby 1992:28). Whilst

there was never an occasion where punters would raise queries with me over my

female colleagues, there were certainly occasions where they would refer

directly to the male manager over all of us. This I felt was due to punters

realising that I was new to the job and probably not well versed in product

knowledge. There were, however, numerous occasions where punters would enquire

to me directly (before female colleagues) questions about results, or even my

opinion, of races or other sporting events. Often there would be remarks such as

"no point asking her, she won't know."

The thrill associated with laying a bet is extremely

attractive to the working classes. It allows not only the dream of economic

betterment in a fashion which defies everything that people are taught about how

one "should" make a living, whilst concurrently offering the kind of

excitement Which breaks up the monotony of daily life. Further, success in the

LBO is accompanied by a sense of competence and skill, which is often lacking in

everyday routine. The reticence among punters to make small talk or discuss

their work and daily routine is an intrinsic part of what it is to be a punter.

Aspects of daily drudgery are left at the door of the LBO, where the

overwhelming majority of conversation revolves around betting, form and key

moments within races.

LBOs foster an impression upon their regulars that there is

an exact science behind betting upon races, which becomes manifest in discourses

concerning knowledge of how to read the form guides, understand them and

demonstrate sagacity in terms of the selection(s) made. Punters, whether

consciously or not, reproduce this myth of science through the very act of

studying these sources of information. The practice becomes ingrained in the

culture of the LBO until it comes to be a quasi structure, separating punters

from other, more casual gamblers. In order to be a successful punter one must

conform to this ritualistic evaluation and understand all of the complexities

which go with it. If a person were to win, consistently, who selected runners

based upon things other than the information presented in the Racing Post

displays as being relevant to the outcome of the race, such as the colour of the

jockey's silks, they would not represent a credible punter, but rather someone

who merely has incredible luck. The complex nature of entering this world keeps

those kinds of people who would disregard information in this way excluded from

the culture of the LBO.

Whilst I do not wish to suggest that gambling in LBOs is some

kind of Masonic club, exclusive only to certain members, 1 feel there is a close

connection between the structures which govern its interaction, the kinds of

influences is exerts over gambling behaviour and the punters who most regularly

use them. LBOs influence gambling behaviour, and who gambles there through their

physical layout, through the ritualistic processes, which have become an

inherent structure within LBO culture and by providing the dream of financial

gains. All of this serves to favour a dream of escape shared by many working

class men and it is no surprise that they are the chief patrons of these

establishments.

Conclusions.

This research has investigated the manner in which the social

setting of the LBO has an influence over the gambling behaviour of its punters.

LBOs, appeal to a particular sense of masculinity; they proffer the dream of

financial gain whilst simultaneously offering escapism, fantasy and the all too

rare feeling of victory and competence. The knowledge required to be a credible

punter is rigorously specialised in terms of knowing how to fill in a betting

slip; to understanding form guides; to reading the market and so on. They play

on the punters' subjective comprehension of probabilities yet simultaneously

lure punters from their quasi-rational approach. All of this serves to produce

and reproduce a dominant identity within the LBO, that of a working class male

who, through his specialised knowledge, seeks to escape financial subordination

and the drudgery of daily life.

The continued dominance of this particular identity is

gradually coming under attack. The impact of Internet gambling, iDTV and

telephone betting are all yet to be discovered. Suggestions that such new

channels for gambling behaviour may come to raise the profile of betting and

increase the number of regular gamblers may be well founded, but this does not

necessarily mean that new groups and new identities will begin to take over LBOs.

Why, if people become comfortable with internet betting, will they not stick

rigidly to this medium? The impact of football betting has yet to reach its

summit whilst being the fastest growing area of LBO gambling, it is still among

the smallest as a percentage. It is therefore too early to predict whether or

not football really is going to affect the mainstay of betting, horses and dogs,

and consequently those who gamble in LBOs. Traditional gender roles may be

gradually being dissolved but there still exist strong structures concerning the

"place" of women in society. It is unlikely that these will change

dramatically in the near future and thus LBOs will probably depend upon men for

the bulk of their patronage for some time yet.

All these factors apart, it is, as one of my older colleagues

told me, an exciting time in the world of bookkeeping. Whilst there is no real

threat to the dominant punter identity at present, the changes taking place

within the industry are bound to have some kind of affect upon the constitution

of LBO regulars. Perhaps LBOs present a last lingering, glimpse into a culture

that may be soon to face its end; perhaps they will remain as they are for some

considerable time yet. Whichever eventuality (if any) comes about in the future,

what is clear is that at present, LBOs demonstrate a great ability to reproduce

themselves as hives for escapism within a working class male context.

Gambling is one of the oldest activities known to humankind,

embroiled as it has been throughout history with the promise of gain. The thrill

and excitement attached to betting on ultimately unknowable outcomes, especially

in what amounts to an unfair and oppressive (in terms of intangible structures)

society goes far beyond the quest for economic gain. As long as we continue to

live in a society that prizes wealth and material possession yet distributes

them unequally then there will always be a place for gambling.

Bibliography.

Beck (1996) Risk Society trans. M. Ritter. London, Sage.

Bergler The Psychology of Gambling. In Herman ed. (1967)

Gambling New York, Harper and Row.

Bernstein (1998) Against the Gods. New York, John Wiley and

Sons inc.

Burgess (1984) In the Field. London, George, Allan and Unwin.

Burkitt (1995) Social Selves. London, Sage.

Clapson (1992) A Bit of a Flutter. Manchester university

Press.

Cohen and Hansel (1956) Risk and Gambling. London, Longman.

de Vaus (1993) Surveys in Social Research 3rd edition.

London, UCL Press.

Dickerson (1984) Compulsive Gamblers. London, Longman.

Downes et. al (1976) Gambling, Work and Leisure. London,

Routledge and Keegan Paul.

Filby The Figures, The Personality and The Bums. Work,

Employment and Society Vol 6 No. 1, 1992 p23-42

Finucane et. al The Affect Heuristic in Judgements of

Risks and Benefits. In Slovic (2000) The Perception of Risk. London,

Earthscan

Fischer The Pull of the Fruit Machine. Sociology Review Vol

43 No.3, 1993 p446-475

Insley, J. A Nation Fond of a Flutter. In The Observer. 12

November 2000

Internet Source Gambling Behaviour in Britain. National

Centre for Social Research http://www.natcen.ac.uklnews/news-gambling-sumfind.htm

Langer (1983) The Psychology of Control. London, Sage.

Lupton (1999) Risk. London, Routledge.

Mintel Leisure Intelligence (August 1998) Horse and Dog

Racing. Mintel International Group Ltd.

Mintel Leisure Intelligence (May 2001) Online Betting.

Mintel International Group Ltd.

Neal (1999) The Role of Gambling in Betting Shops During

Work and Leisure Hours. paper delivered to the Urban Labour and Leisure

Conference, Leicester

Neal You Lucky Punters. Sociology Vol 32 No.3, August 1998

p581-600

Newrnan (1972) Gambling, Hazard and Reward. London, The

Athelone Press

Nibbert (2000) Hitting the Lottery Jackpot. New York,

Monthly Review Press

O'Connell-Davidson and Layder (1994) Methods, Sex and

Madness. London, Routledge

Rosecrance Why Regular Gamblers Don't Quit. Sociological

Perspectives Vol 29 No.3, 1986 p357-378

Smith and Preston Vocabularies of Motives for Gambling

Behaviour. Sociological Perspectives Vol 27 No.3, 1984 p325-348

Sprotson, Erens and Orford The Future of Gambling in

Britain. British Medical Journal Vol 32 1, November 2000 p 1291-1292

Treweek and Linkogle (2000) Danger in the Field. London,

Routledge.

Warman, J. Women: Betting the Devil You Know. In The

Guardian. 27 February 1996

Zola Observations on Gambling in a Lower-Class Setting.

In Becker (1963) The Other Side. London, The Free Press of Glencoe Macmillan

Ltd.